Could we kill two diseases with one campaign?

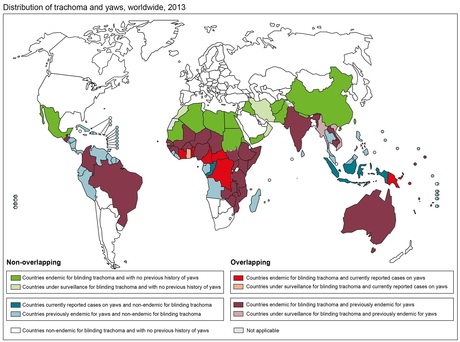

British researchers have proposed that the World Health Organization’s planned mass treatment campaign to eradicate the tropical disease yaws from the planet by 2020 should be integrated with a WHO-led project to eliminate another common disease of the world’s poor — trachoma — with the same deadline.

Yaws, which affects skin, bone and cartilage, no longer exists in Australia, but trachoma — commonly known in Australia as ‘sandy blight’ — remains a leading cause of blindness and vision problems among Indigenous Australians, particularly those living in remote communities.

The common element to the two programs is the antibiotic azithromycin, which is on the WHO’s List of Essential Medicines. It is highly effective against the causative agent of yaws, the spirochaete bacterium Treponema pallidum ssp pertenue, and against the intracellular bacterium that causes trachoma, Chlamydia trachomitis. In 2010–2011, a randomised trial in Papua New Guinea demonstrated that a single dose of azithromycin was at least as effective as an intramuscular penicillin injection in curing yaws.

A discussion paper published on 3 December in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases suggests that the geographic overlap between yaws and trachoma in tropical regions like central Africa and Papua New Guinea offers opportunities for synergies between the yaws and trachoma eradication projects. Dr Anthony Solomon, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, is Chief Scientist to the WHO’s Global Trachoma Mapping Project and the lead author on the paper, titled ‘Trachoma and Yaws: Common Ground?’.

Renowned Australian eye surgeon Professor Fred Hollows was a leading proponent for eliminating trachoma as part of a broader program for improving eye health in Indigenous Australians. In 1975, Professor Hollows obtained a $1.4 million grant from the Commonwealth Department of Health to establish the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program.

He and wife Gabi spent two years traversing Australia in 4WD vehicles, examining and treating more than 100,000 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders for eye problems. Professor Hollows sought to raise public awareness of the issue, pointing out that 94% of blindness in Indigenous Australians was preventable.

Professor Hollows died of pancreatic cancer in 1993. The Fred Hollows Foundation, led by Gabi Hollows, continues his work.

In 2010, the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey examined 1694 Indigenous children aged between five and 15, and 1189 Indigenous adults from 30 remote and rural communities across Australia, to determine the prevalence of trachoma. The results, reported in the Medical Journal of Australia, told an all-too-familiar story: blinding endemic trachoma remains a major public health problem in many Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander communities.

The study, headed by Professor Hugh Taylor of The University of Melbourne, found that many Indigenous communities still have a serious problem with blinding trachoma and trachoma scarring of the eyes. The average infection rate in children was 3.8%, ranging from 0.6% in Indigenous children in major cities to 7.3% in very remote communities. 50% of remote Indigenous communities had an infection rate greater than 5%, the level at which trachoma is considered endemic.

Among adults examined, 15.7% had eye scarring from trachoma, 1.4% had trachomatous trichiasis (TT), or inflammation of the conjunctiva, and 0.3% suffered from corneal opacity (CO) due to trachoma. The highest rate for trachoma scarring in any community was 58.3%; for TT it was 14.6% and for CO it was 3.3%.

The WHO trachoma project holds out the promise of finally realising Professor Hollows’ ambition to eliminate trachoma from Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander communities, while Australia’s near-neighbour, Papua New Guinea, would be a major beneficiary of both the trachoma and yaws projects.

But Professor Solomon and his colleagues identify several issues that could be encountered in a joint campaign against trachoma and yaws in regions where the diseases are co-endemic.

Where the yaws program seeks to eradicate the disease completely, the trachoma program aims only to reduce the disease to a level where it is no longer a public health problem, not to eliminate it completely. Its stated aim is “the reduction of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity or mortality to a locally acceptable level”.

The paper describes a previous “half-hearted” attempt to eliminate yaws in the 1970s, which was unsuccessful. Attempts to control trachoma with tetracycline ointment in the 1950s were also unsuccessful.

Another potential problem for a joint campaign against yaws and trachoma is that different administration protocols are involved. The recommended azithromycin dosage for yaws is higher and involves a one-off dose, with potential follow-up treatments of individual cases where necessary. The trachoma program, however, will involve annual treatments for every community member for five years.

Melatonin helps to prevent obesity, studies suggest

In an experiment carried out in rats, chronic administration of melatonin prevented obesity to a...

Personality influences the expression of our genes

An international research team has used artificial intelligence to show that our personalities...

Pig hearts kept alive outside the body for 24 hours

A major hurdle for human heart transplantation is the limited storage time of the donor heart...